American manual alphabet

The American Manual Alphabet (AMA) is a manual alphabet that augments the vocabulary of American Sign Language.

Letters and digits

The letters and digits are signed as follows. In informal contexts, the handshapes are not made as distinctly as they are in formal contexts.

-

1

1 -

2

2 -

3

3 -

4

4 -

5

5 -

6

6 -

7

7 -

8

8 -

9

9 -

10

10

The manual alphabet can be used on either hand, normally the signer's dominant hand – that is, the right hand for right-handers, the left hand for left-handers.[1] Most frequently, the manual alphabet is signed just below the dominant shoulder of the signer. When used within other signs or in a context in which this is not plausible, this general rule can be disregarded.[2]

J and Z involve motion. J is I with a twist of the wrist, so that the little finger traces the curve of the printed form of the letter; Z is an index finger moved back and forth, so that the finger traces the zig-zag shape of the letter Z. Both of these "tracings" are made as seen by the signer if right-handed, as shown by the illustrations in this article. When signed with the left hand, the motions are in mirror image, therefore unreversed for the viewer. However, fluent signers do not need to "read" the shapes of these movements.[3]

In most drawings or illustrations of the American Manual Alphabet, some of the letters are depicted from the side to better illustrate the desired hand shape. For example, the letters G and H are frequently shown from the side to illustrate the position of the fingers. However, they are signed with the hand in an ergonomically neutral position, palm facing to the side and fingers pointing forward.

Several letters have the same hand shape, and are distinguished by orientation. These are "h" and "u", "k" and "p" (thumb on the middle finger), "g" and "q" and, in informal contexts, "d" and "g/q". In rapid signing, "n" is distinguished from "h/u" by orientation. The letters "a" and "s" have the same orientation, and are very similar in form. The thumb is on the side of the fist in the letter "a", and in front for "s". When used within fingerspelled English words, letters of the manual alphabet may be oriented differently than if they were to stand alone. [2]

Rhythm, speed and movement

When fingerspelling, the hand is at shoulder height; it does not bounce with each letter. A double letter within a word is signed in different ways, through a bounce of the hand, a slide of the hand, or repeating the sign of a letter.[4] Letters are signed at a constant speed; a pause functions as a word divider. The first letter may be held for the length of a letter extra as a cue that the signer is about to start fingerspelling.

Uses

Fingerspelling is primarily used for borrowing words from English. It is typically only used in a specific set of circumstances. The following are words that might need to be fingerspelled: proper names, brand names, place names, and all other words that do not have a conventional sign.[5] In other instances, use fingerspelling sparingly.

Changes and variations in the manual alphabet

Like other languages, American Sign Language is constantly evolving. While changes in fingerspelling are less likely, slight changes still occur over time. The manual alphabet looks different today than it did merely decades ago. A prime example of this pattern of change is found in the "screaming 'E'". Older generations of deaf individuals still insist that the "E" handshape requires that the thumb make contact with the tips of the index and middle fingers. Meanwhile, younger generations are beginning to produce a handshape that separates the thumb from the other fingers on the lower end of the palm.[6]

English and the manual alphabet

Since fingerspelling was originally developed in order to incorporate the English language into sign language, it is very closely linked to English. Studies have shown that deaf individuals process reading and fingerspelling similarly. As a result, fingerspelling has had a profound impact on the literacy of deaf and hard of hearing children. This conclusion is widely accepted, but the debate lies in which methods of teaching best utilize this relationship.[7]

Sign Language and its Phonetics

Phonetics does not have to be constricted to just speech but it can also be used when signing to others. When signing, the person's expressions could greatly determine the outcome of what they are trying to communicate to the other person. For example, if the signer was trying to sign that they were mad, they would use facial expressions and body language to really determine how they were feeling. Although spoken language also uses these forms of expression, they are not relied on as heavily as Sign Language. The phonetics of verbal speech and sign language are similar because spoken dialect uses tone of voice to determine someone's mood and Sign Language uses facial expressions to determine someone's mood as well. Phonetics does not necessarily only relate to spoken language but it can also be used in American Sign Language (ASL) as well. When signing in ASL, people will not sign words the same way they are spoken either. The relationship between spoken dialect and ASL varies because there is association between certain signs and their words and they are signed differently because ASL is not signed the same way it is spoken.[8][9]

Gallery

-

A

A -

B

B -

C

C -

D

D -

E

E -

F

F -

G

G -

H

H -

I

I -

J

J -

K

K -

L

L -

M

M -

N

N -

O

O -

P

P -

Q

Q -

R

R -

S

S -

T

T -

U

U -

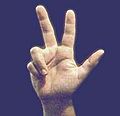

V

V -

W

W -

X

X -

Y

Y -

Z

Z

References

- ^ Tennant, Richard A. (1998). The American Sign Language handshape dictionary. Brown, Marianne Gluszak. Washington, D.C.: Clerc Books, Gallaudet University Press. ISBN 978-1563680434. OCLC 37981448.

- ^ a b Valli, Clayton; Ceil, Lucas (2000). Linguistics of American Sign Language (3rd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press. p. 66. ISBN 9781563682186.

- ^ Stokoe, William C. (2005-01-01). "Sign Language Structure: An Outline of the Visual Communication Systems of the American Deaf". The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 10 (1): 3–37. doi:10.1093/deafed/eni001. ISSN 1081-4159. PMID 15585746.

- ^ "ASL.Land". asl.land. Archived from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ Geer, Leah C; Keane, Jonathan (2017-01-09). "Improving ASL fingerspelling comprehension in L2 learners with explicit phonetic instruction". Language Teaching Research. 22 (4): 439–457. doi:10.1177/1362168816686988. ISSN 1362-1688. S2CID 151792040.

- ^ M., NOMELAND, MELVIA (2011). DEAF COMMUNITY IN AMERICA: HISTORY IN THE MAKING. MCFARLAND. ISBN 978-0-7864-6397-8. OCLC 1154409793.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Scott, Jessica A.; Hansen, Sarah G.; Lederberg, Amy R. (2019). "Fingerspelling and Print: Understanding the Word Reading of Deaf Children". American Annals of the Deaf. 164 (4): 429–449. doi:10.1353/aad.2019.0026. ISSN 1543-0375. PMID 31902797. S2CID 208619892.

- ^ Brentari, Diane (2019). "Sign Language Phonology". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ Crasborn, Onno (2019). "Phonetics, Phonology, and Prosody" (PDF). Retrieved November 20, 2023.

External links

- Practice fingerspelling receptive in real life Practice "reading" fingerspelling using real life videos.

- Fingerspell A free, online practice site with realistic, animated ASL fingerspelling.

- ASL Fingerspelling Resource Site Free online fingerspelling lessons, quizzes, and activities.

- ASL Fingerspelling Online Advanced Practice Tool Test and improve your receptive fingerspelling skills using this free online resource.

- Fingerspelling Beginner's Learning Tool Learn the basic handshapes of the fingerspelled alphabet.

- ASL alphabet Image and video examples of the English alphabet being signed in American Sign Language.

- Manual Alphabet and Fingerspelling Further information, fingerspelling Tips and video example of ASL Alphabet.

- v

- t

- e

- American

- Catalan

- Chilean

- Esperanto

- French

- Hungarian

- Irish

- Japanese

- Korean

- Nepali

- Polish

- Portuguese

- Russian

- Spanish

- Ukrainian

- Yugoslav