Name of Aruba

Portolan Chart of the Known World (1516) depicts the eastern coasts from Americas to India. | |

| Pronunciation | /əˈruːbə/ |

|---|---|

| Language(s) | Hispanized Arawak |

The origin and meaning of the name of Aruba are uncertain due to limited knowledge about the Caquetío language spoken by the Caquetío people who lived on the island before European colonization. However, the name "Aruba" is believed to be a Hispanized Indigenous name of Arawak origin.[1][2]

Johan Hartog mentions in Aruba: Past and Present—From the Time of the Indians until Today, that the name of the island appears for the first time, as far as we know, in the Historia Natural y General de las Indias, vol. XX [es], written in 1526 by Fernandez de Oviedo. Oviedo writes:[a]

To the west of the island of Aves lies the island of Boynare; further west is another island called Corozante; even further west is the island called Aruba located. These names are spelled differently by many new cosmographers on some maps.[3]

In fact, this seems to have been the case very often. The frequent usage led to the name Aruba gaining prominence over time.

When the Spaniards first arrived on the island, c. 1500, they called it Orua, Oruba, and Ouruba. Later, names such as Curava, Uruba, Arouba, and Aruba were used.[3]

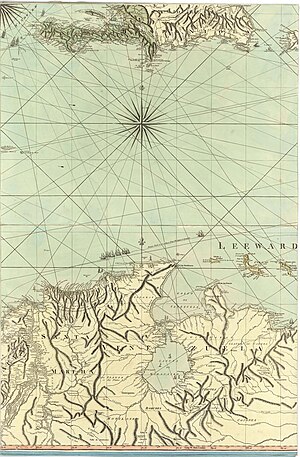

The Portolan Chart of the Known World (Naples, 1516) by the Genoese cartographer Vesconte Maggiolo[4] is the oldest map where the name "Aruba" is mentioned.

Etymology

It's important to note that the following theories and explanations are based on limited historical information, and the true meaning and origin of the name "Aruba" may still remain uncertain.

Aruveira

On Tuesday, November 5, 1493, Christopher Columbus sent two boats ashore on an island he named Santa María de Guadalupe (Guadeloupe). The purpose was to capture some indigenous people who could provide information about the surrounding land, including the direction and distance to Hispañola. According to accounts given by an indigenous women, it was revealed that to the south were many islands, some inhabited and uninhabited. These islands were referred to as Jaramachi, Cairoato, Huino, Buriari, Aruveira, Sixbei. Additionally, it was mentioned that the mainland was vast in size.[5]

Ouruba, Curaba

During the early colonial period, Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao were considered a single entity. The order in which they were mentioned varied, but documents from that time treated them as a collective. Aruba and Bonaire were referred to as islas adyacentes, or adjacent islands, of Curaçao. The initial mention of these islands occurred in the content of a Royal Decree on November 24, 1525, "Real Cedula a los Oidores de Santo Domingo para que amparan a Juan de Ampiés en la posecion de las islas de Curacao, Curaba y Buynare, que le habian" (Royal Decree to the Auditors of Santo Domingo to protect Juan de Ampues in the possession of the islands of Curacao, Curaba, and Buynare, which had been granted to him).[6][7][8][9] However, in a document from November 15, 1526, Charles V mentioned Aruba first as "Ouruba y Curacao y Buynare que estan en comarce de la tierra firme" (Ouruba and Curaçao and Buynare, which are located in the mainland region). Further references in the same letter invariably show the following order and spelling: "Corazao y Oruba y Buynare".[10]

Orua, Oruba

The origin of "Aruba" is often associated with the presence of gold on the island, mainly due to early Spanish writings in which it is referred to as Orua and Oruba. Some have suggested that the latter name could be a contraction of oro hubo, which means "there was once gold," leading to the assumption that Aruba was a land abundant in gold. However, this name would be incorrect because there is no evidence that the Spanish colonizers discovered gold on the island. In fact, a letter from Juan de Ampiés, Lord of Curaçao, Aruba, and Bonaire, to Emperor Charles V in 1528 implies that there was no gold on Aruba before the island was named. In the letter, Ampiés informed the king that the islands under his jurisdiction had already been declared "useless islands" (islas inútiles) by Admiral Diego Columbus in 1513, based on the information received.[11]

Bay of Orubá

One theory suggests that the Spaniards may have named the island Isla de Oruba, possibly related to the Bay of Orubá located in Lake Maracaibo. The Spaniards were aware of this name and applied it to the island when they heard a similar-sounding name. They knew that the same indigenous population living on Oruba also inhabited the Bay of Orubá and shared the same customs.[12] Additionally, "Aruba" could be derived from the indigenous word "oruba," which means "well-placed" or "well-situated."[13]

Oirubea

The name "Aruba," also spelled as Oruba or Orua, is believed to originate from the Tupí-Guaraní word oirubea, which means "companion."[14] This suggests that Aruba was seen as the companion of other nearby places, such as Paraguaná or Curaçao. The Caribbean people were seafaring individuals and likely brought many linguistic influences to the Caribbean coast of South America and the Arawak regions in northwestern Venezuela. The Arawak and Caribbean languages have been significantly influenced by the Tupí-Guaraní language(s).[b]

In the book Arte, y bocobulario de la lengua guarani by Father Ruiz de Montoya, the word ñoiru/yru, is mentioned, which means acompañado (accompanied). When the suffix -bae, a participle meaning -ing, is added, the resulting word is "oirubae", meaning accompanying.[15][16]

Ora Oubao

Oruba could possibly have a connection to the Caribbean word oraoubao.[12] The French-Dominican missionaries Breton, Labat, and Du Terte suggest that the words "ora," which means "shell," and "oubao," which means "island," can be combined to form "shell island".[17]

In 1665, while Breton was staying on the island of Wáitukubulí (Dominica), he created a French translation of an island-Caribbean dictionary called Dictionnaire caraïbe-français. This dictionary mainly consists of Arawak words but also includes Carib elements.[18] In this dictionary, the term oüatabüi óra is mentioned, which can be translated as la coquille de Lambis or "the shell of queen conch".[19] Although oúbao means "island," the Kalina word has expanded in meaning and also includes the islands of the Antilles or the Caribbean region.[20]

Oroba

In a book titled Beschrijving van het eiland Curaçao en de daar onder hoorende eilanden ("Description of the island of Curaçao and the islands belonging to it") from 1773, the island is referred to as Oroba, and it is mentioned that it also known as Oruba or Aruba. The book provides a description of Oroba's geographical location and its significance. Here is the passage from the book where Oroba is mentioned:

Oroba, by anderen Oruba of Aruba, zeven of agt mylen Westwaards van Curaçao gelegen, is kleinder dan Bon-Aire, maar nader aan Spaansche Kust. Het zelve dient tot een gelyk oogmerk als het eerste, en men haalt 'er mede leeftogt van daan, zo voor de Ingezetenen als voor de Slaven; zynde ook door eenige Indianen bewoond, en de Maatschappy houd 'er insgelyks een Kommandeur, onder Kommandeur, en weinige Soldaten.

Nergens is ons voorgekomen, dat de Franschen in hunne onderneemingen tegen Curaçao, den minsten aandacht naar deeze twee Eilanden gewend hebben; dezelve ongetwyffeld der moeite niet waardig oordeelende, tot het doen eener landinge; ondertusschen daarze evenwel beiden van zeer veel noodzakelykheid voor Curaçao zyn.[21]Oroba, also known as Oruba or Aruba, is located seven or eight miles west of Curaçao. It is smaller than Bonaire but closer to the Spanish coast. It serves a similar function as the previous island, providing food for both the residents and the slaves. It is also inhabited by some indigenous people, and the company maintains a commander and a few soldiers there.

We have not come across any case in which the French, in their operations against Curaçao, paid the slightest attention to these two islands. Undoubtedly, they consider them not worth landing on. However, both islands are still of great importance to Curaçao.

Uruba

In a newspaper article from De Curaçaosche courant of 1835, it is mentioned that a sixteenth-century Italian historian in the service of the Spanish Crown, Petrus Martyr (also known as Pietro Martire d'Anghiera), stated that the Gulf of Darién originally named the Gulf of Urabá, which means "gulf of canoes". The term Uru in the language of the people of Uraba means "canoe"[22] and ba is a preposition meaning "of", so Uruba means "of the canoes"[23] It is suggested that Aruba could have a similar meaning.[14]

Arubaes

In 1607, a report signed by the cabildo (municipal council) of Maracaibo mentions the Aliles, Toas, Saparas, and the Arubaes as indigenous groups that had allied themselves against the Spaniards. This report is called Información sobre la Nueva Zamora, hecha por el Capitán Juan Pacheco Maldonado and was published in the Relaciones Geográficas de Venezuela ("Geographical Relations of Venezuela"). The Arubaes refer to the Caquetío population of Aruba.[24]

Jossy Mansur, an amateur historian from Aruba, suggested that "Aruba" could also have its origin in the ethnonym of the indigenous population who lived on the island, known as the Arubaes (Arubanas in the 18th century).[c] However, it remains unclear whether these indigenous people were the original Caquetío inhabitants of the island when the Spaniards first arrived on Aruba. By 1526, when the island was initially referred to by its original name "Aruba," the Caquetío people had already been deported, and those who later returned were not necessarily the original inhabitants. The later inhabitants of Aruba became known as Arubaes and Arubanas. Therefore, it is uncertain whether Aruba was named after the inhabitants or if the inhabitants were named after Aruba.[25]

Notes

Sources

- Anghiera, P.M. d' (1912). "Wellesley College Library". De orbe novo, the eight Decades of Peter Martyr d'Anghera. New York, London: G.P. Putnam's Sons.

- Breton, R. (1991). Karthala (ed.). Dictionnaire caraïbe-francais 1665 (PDF) (in French). ISBN 978-2-86537-907-1.

- Buurt, G. van; Joubert, S. (1997). Stemmen uit het verleden : Indiaanse woorden in het Papiamentu. Willemstad, Curaçao: Joubert. ISBN 99904-0-145-4. OCLC 68282509.

- Campos Reyes, D.W. (2004). "The Origin and Survival of the Taíno Language" (PDF). Issues in Caribbean Amerindian Studies. Retrieved 2023-07-01.

- Colón, F.; Roman, F. (1892). "Robarts - University of Toronto". Historia del almirante don Cristóbal Colón en la cual se da particular y verdadera relación de su vida y de sus hechos, y del descubrimiento de las Indias occidentales, Ilamadas nuevomundo; escrita por don Fernando Colón, su hijo (in Spanish). Madrid [Impr. de T. Minuesa].

- Dijkhoff, R.C.A.F. (1997). Tanki Flip / Henriquez: an Early Urumaco Site in Aruba (Thesis). Leiden University. Retrieved 2023-07-04.

- Goslinga, C.C. (1956). "Juan De Ampues: Vredelievende Indianenjager". De West-Indische Gids. 37: 169–187. doi:10.1163/22134360-90000037. JSTOR 41835651.

- Goslinga, C.C. (1971). The Dutch in the Caribbean and on the Wild Coast, 1580-1680. Assen: Van Gorcum. ISBN 978-90-232-0141-0.

- Hamelberg, J.H.J. (1898). "2e Jaarverslag van het Geschied-, Taal-, Land- en Volkenkundig Genootschap" [2nd Annual Report of the Historical, Linguistic, Land, and Ethnographic Society]. Geschied-, Taal-, Land- en Volkenkundig Genootschap. Amsterdam.

Gegevens betr. Juan de Ampués.

- Hartog, J. (1961). Aruba : Past and Present : From the Time of the Indians until Today. Translated by J.A. Verleun. Oranjestad: D.J. de Wit.

- Hering, J.H. (1779). Beschryving van het Eiland Curaçao en de daar Onder Hoorende Eilanden, Bon-Aire, Oroba en Klein Curaçao [Description of the Island of Curaçao and the Islands Associated with It, Bon-Aire, Oroba, and Klein Curaçao]. Amsterdam. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- Hoyer, W.M. (1938). "De Naam Aruba". New West Indian Guide / Nieuwe West-Indische Gids. 20 (1): 370–371. doi:10.1163/22134360-90000762.

- Menkman, W.R. (1942). De Nederlanders in het Caraibische zeegebied waarin vervat de geschiedenis der Nederlandsche Antillen. Amsterdam: P.N. van Kampen. OCLC 615217900.

- Nogueira, Baptista Caetano d'Almeida (1876). "Boston Public Library". Apontamentos sobre o Abañeeñga : tambem chamado Guarani ou Tupi, ou lingua geral dos Brasis.

- Oliver, J.R. (1989). The Archaeological, Linguistic and Ethnohistorical Evidence for the Expansion of Arawakan into Northwestern Venezuela and Northeastern Colombia (Thesis). University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign (UIUC). Retrieved 2023-04-27 – via UCL Discovery.

- Ruiz de Montaya, Antonio (1640). "John Carter Brown Library". Arte, y bocobulario de la lengua guarani. Madrid: Iuan Sanchez.

- Vespucci, A.; Columbus, C. (1992). Letters from a new world : Amerigo Vespucci's Discovery of America. New York: Marsilio. Retrieved 2023-07-03.

References

- ^ Menkman 1942, p. 7.

- ^ a b Buurt & Joubert 1997, p. 48.

- ^ a b Hartog 1961, p. 32.

- ^ Caraci, G. (1937). "A Little Known Atlas by Vesconte Maggiolo, 1518". Imago Mundi. 2: 37–54. doi:10.1080/03085693708591833. ISSN 0308-5694. JSTOR 1149833.

- ^ Colón & Roman 1892.

- ^ Goslinga 1956, p. 175.

- ^ Hamelberg 1898, p. 14.

- ^ "PANAMA,233,L.2,F.219V-221V - Requerimiento que ha de hacer Juan de Ampies". PARES. Retrieved 2023-07-05.

- ^ "PANAMA,233,L.2,F.205V-214V - Licencia para rescatar y contratar en Coro a Juan de Ampies". PARES. Retrieved 2023-07-05.

- ^ Hartog 1961, p. 28.

- ^ Hoyer 1938, p. 370.

- ^ a b Hoyer 1938.

- ^ Goslinga 1971, p. 264.

- ^ a b Hartog 1961, p. 33.

- ^ Ruiz de Montaya 1640.

- ^ Nogueira 1876.

- ^ Hartog 1961.

- ^ Campos Reyes 2004.

- ^ Breton 1991, p. 203.

- ^ Breton 1991, p. 294.

- ^ Hering 1779, p. 76.

- ^ Anghiera 1912, p. 226.

- ^ Anonymous 1835. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAnonymous1835 (help)

- ^ Oliver 1989, p. 209.

- ^ a b Dijkhoff 1997.